Brief Description:

Habit Two, the Habit of the Forest and the Trees, identifies the cultural dimensions of a client’s interaction with the “Law.” In assessing the cultural dimensions of the “Law,” Habit Two looks expansively at the rules, the legal institutions and the key decision makers and players involved in the case or matter. Thus, throughout this post, we use the “law” to include legal rules and statutes, as well as legal actors (judges, adversaries, administrators, probation officers, etc.). Habit Two points out aspects of a case that are important for legal success:

- Identify aspects that may catch a judge or decision maker’s focus or contempt

- Acknowledge why the client may see the lawyer as part of a hostile legal system

- Identify how to push the legal system to adapt to client’s perspective or claim

- Conversely, ask how the client might adapt to the legal system’s norms and values

Having laid the groundwork for a more complete understanding of the client in Habit One, Habit Two allows the lawyer to transition from a potential overemphasis on the lawyer-client relationship towards a more holistic and well-balanced view of the case. In Habit Two, the lawyer shifts his or her attention to the client’s legal objectives, the merits and weaknesses of the client’s case as seen by the law, and the way that the client’s legal claim fits into the client’s world more generally. With these clearly in focus, the lawyer can attend to his or her central goal: strengthening the client’s legal claim. Habit Two, therefore, is designed to help the lawyer sort through the many factors shaping their representation.

Habit Two sharpens the lawyer’s focus on the relationship that actually matters: the client’s world and the ways in which that world interacts with the world of the law. By contextualizing the client’s problems and perspectives within the legal system, Habit Two prepares the lawyer to effectively represent the client and identify potential legal solutions.

More Detail:

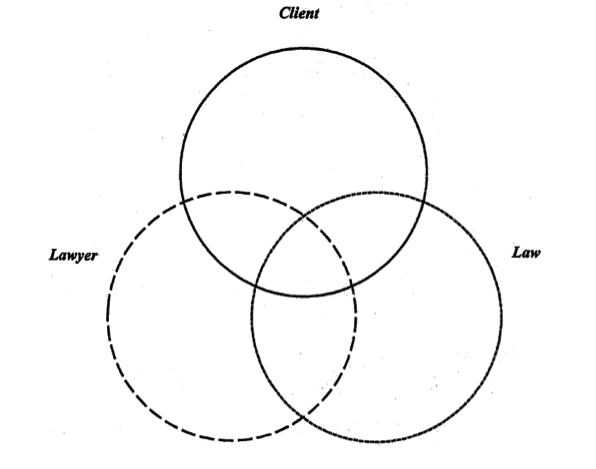

Habit Two uses a three-way Venn diagram to identify and analyze differences and similarities between a client, her lawyer and the law.

While the most complex to explain and learn, Habit Two also offers the biggest payoff—a clearer frame by which to internalize the many cultural dynamics in a case while keeping one’s eyes centrally on the client’s legal claim.

Teaching Habit Two

Exercise 1. Three Rings in Action

Running the Exercise (15 minutes to do & 10-15 minutes to debrief)

1. The Client-Law Dyad:

- Ask students to take a sheet of paper and draw a Venn diagram with two circles (one representing their client, and the other representing the law).

Give students 4 minutes to list the similarities and differences between their clients and the law in these circles. During this portion of the exercise, you may ask the following guiding questions:

- “What does the law favor about your client?” (client-law overlap);

- “What does the law disfavor about your client?” (client-only circle); and

- “Where does the law diverge from your client’s case?” (law-only circle).

Guiding questions for client-law dyad:

- How can I increase the overlap between my client and the legal system?

- What additional facts can I learn about my client to strengthen the case?

- How can I change the relevant facts to support my client’s case?

- Can I increase the law’s receptiveness to my client’s claim?

- Can I advocate for changes in the underlying law itself?

The diagram above features two circles overlapping only in part; the circle on the top left represents the client’s world and the circle on the bottom right represents the world of the law. The area of overlap between the two circles, when filled out, contains characteristics shared by the client and the legal system.

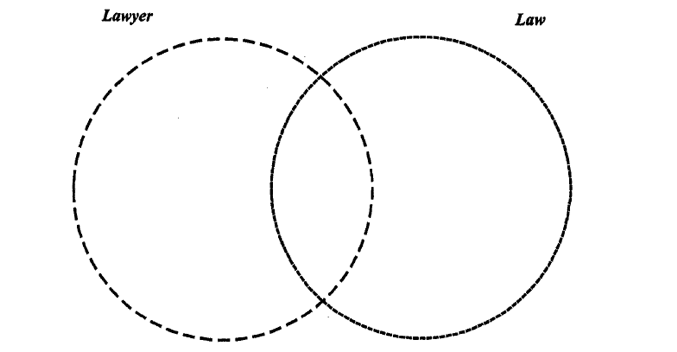

The Lawyer-Legal System Dyad:

- Have your students draw another Venn diagram with two overlapping circles (one representing themselves as the lawyer, and the other representing the law). (Note that, depending on the case’s procedural posture, the law circle may represent different actors, including: the legal system, judge, hearing officer, opposing counsel, or jury.)

- Give them 4 minutes to list similarities and differences between themselves and the law.

This diagram features two circles side-by-side, also overlapping in part; the circle on the left represents the lawyer’s world and the circle on the right represents the world of the law (this is the same bottom circle as in the previous diagram). The area of overlap between the two circles, when filled out, contains characteristics shared by the lawyer and the legal system.

The Lawyer-Client Dyad: Have students refer to their Venn diagram from Habit One.

This third diagram features the circles from Habit One—namely, the lawyer’s circle on the bottom left and the client’s circle on the top right. The area of overlap between the two circles, when filled out, contains characteristics shared by the lawyer and the client.

The Three Rings in Action:

- Instruct your students to draw another Venn diagram, this time with three overlapping circles (the first representing the lawyer, the second representing the client, and the third representing the law). This final drawing will allow them to conceptualize everything they have analyzed up to this point in a holistic manner.

This fourth diagram juxtaposes the previous diagrams, depicting the three rings at once: that of the client (on the top center), the lawyer (on the bottom left) and the law (on the bottom right). The area of overlap between two circles represents characteristics shared by those two worlds. For example, the area of overlap between the client and the law lists the following shared attributes: not a teenage parent; no evidence of harm. The area of overlap between the lawyer and the law lists the following characteristics: shared respect for motion to dismiss petition; concern for irregular school attendance; concern regarding crack cocaine in home. And the area of overlap between the client and the lawyer lists: older sisters with children; family history of asthma; lived with extended family; has older brothers. Meanwhile, each circle has areas that do not overlap with the others. For the client, these non-shared characteristics are: single; 16 years old; not a parent; poor right now; history of crack cocaine in home; DCYF involvement. For the lawyer, the unique attributes are: loved school; one home as a child; 41 years old; mother of two; no history of DCYF involvement; upper middle class; married. And for the law, the non-shared perspectives are: Rachel is a troubled teen in a troubled home; harm and danger are right around the corner.

Debriefing Exercise 1:

In this debrief, we want to gather student perspectives and offer our own insights into what it means to be an effective legal advocate.

Compared to the client-law diagram, what do you notice about the lawyer-law diagram? This open question encourages law students to think about the ways in which they now resemble the more powerful law and the ways in which the legal system extols their “virtues.” For example, compared to their clients, the high degree of overlap between the lawyer and the law can be disconcerting for a client whose primary interactions with the legal system have been negative or disempowering. A client, therefore, may at first be rightly skeptical of their lawyer’s effectiveness or good intentions. With this in mind, the lawyer’s role is to ensure that this initial disconnect does not interfere with effective legal representation—that the lawyer’s legal expertise is properly channeled towards empowering their client, not alienating them. For example, the student can explain the law to a client and express concerns about the fairness of a provision or the student can explain how they will meet the legal standard using language the client understands. Most importantly, the student can remain vigilant even if the client expresses doubt about the student’s loyalty, and understand why the client might feel this way.

Why might it be important to think about the lawyer, the client, and the law in tandem? We offer this question to get our students to think deeply about the complexity of legal representation. Most students have never served as a “spokesperson” for another in a professional capacity. With this in mind, it is important for students to distinguish their own background, culture, and perspectives from their clients (i.e. Habit One). Even more importantly, students must begin to conceptualize their role in advancing their client’s interests against the backdrop of the law.

Which of the three dyads is most important for effective legal representation and why? The answer, most students will say, is the client-law dyad. While Habit One offered students the opportunity to think about how similarities and differences between themselves and their clients tug on effective representation, Habit Two builds on this initial framework by then asking students to refocus their energies on their client’s case from a legal, not a heuristic, perspective. Increasing the overlap between the client and the law, therefore, should be the lawyer’s biggest priority. We discuss these concepts in greater detail below.

Habit Two – Using lists to chart the similarities and differences

Exercise 2.

Like Habit 1, Habit 2 analysis can also be done by creating lists. These lists can precede, follow or be used as a substitute for the three rings.

1. Preliminary questions

Teachers can begin by asking students to reflect on their general sense of connectedness or disconnectedness from their clients, focusing on individual components of separation and connection. The goal is for students to think about their clients in as much three-dimensional detail as possible, so as to avoid the temptation to lump clients into large categories or to analogize to earlier clients with superficially similar needs. The following questions might help prompt students’ thinking as they engage in this preliminary reflection:

- What is your specific knowledge about this client’s life?

- What do you know about this client’s day?

- What is it like to speak with this client?

- What does this client’s voice sound like, both literally and figuratively?

- What makes this client different from all your other clients

2. Re-visit Habit One

Next, teachers can invite students to reflect back on Habit One, identifying the ways in which their clients’ cases particularly move them, trouble them, interest them, annoy them, or otherwise affect their work. If they find themselves feeling less invested than average in the case, invite them to try to identify aspects of the case that may lead to that sense of estrangement. Teachers may point out that those items may stem from areas of difference between them (the students) and their clients. Conversely, if they feel exceptionally invested in their cases, invite them to identify the aspects of the cases that draw them in. In general, those may well be issues of similarities between them and their clients.

3. The Law-Client Relationship

Students can then move on to consider the values and norms of the legal system relevant to their clients’ legal claims. In different cases, different aspects or decision-makers of the legal world may be relevant: a particular judge, an administrative officer, a prospective jury, a forensic evaluator in a custody case, the pre-sentence probation officer, or the legal text and circuit interpretation of that text. In some situations, they may even want to use particular legal opponents as the representatives of the legal system. As there are many different aspects or players who can represent the legal system, students should choose to focus on one that is especially salient to them and the case in that moment.

Students can then consider strong points and weak points of the client’s claim from point of view of the law, legal system or decision-maker, as the case may be, by asking themselves: what are some characteristics and values of a “successful client” – one whose legal position will be recognized and rewarded? They may want to identify hot-button issues: of all the characteristics listed, which loom largest for the law, legal system or decision-maker?

Students may then try to approach this dyad from the client’s perspective, asking themselves: how important is the legal claim to this client, right now? In considering this question, students should keep in mind the individuality of the particular client in this specific case context.

4. The Law-Lawyer Relationship

Students may then proceed to consider the values and norms of the legal system or decision-maker relevant to the ethical and rewardable legal claims of their clients. Of all the characteristics they came up with, which loom largest for the legal system?

Then, students can think about the extent to which they, as representatives of the law, share the values and norms of the legal system and decision makers above. When students find that they share many similarities with the law, they may come to understand why the client might perceive them as synonymous with the law and part of a hostile or impenetrable legal system.

5. Client-Law-Lawyer All at Once

At this point, teachers may explain to students that the key step in building a winning case is to refocus on the relationship that matters most of all—that between the client and the law—and to generate ideas on how to increase the common ground between the two. These questions may help prompt some ideas:

- Can I shift the law’s perspective to encompass more of the client’s claim?

- What additional facts can I use to strengthen the case?

- Do my current strategies in the client’s case require the law or the client to adjust perspectives? What additional facts or characteristics are needed to strengthen the case?

Finally, students (or lawyers) may bring themselves back into the picture, asking: How can I, as the lawyer, shift closer to my client’s areas of concern, especially those that are relevant to the legal world’s values?

Key Takeaways from Performing Habit Two

This analysis jolts the lawyer out of the automatic pilot that may lead him or her to lump cases together and to neglect the individuality of a particular client in a particular case context. It also guards against her being overly distracted by her similarities and differences with the client, and refocuses her on the job of enhancing the chances of legal success of the claim.

The three rings allow the lawyer to identify a clear area of relevant similarities and differences between the lawyer and client and also identifying irrelevant similarities and differences between lawyer and client. The three rings also identify the ways in which differences between the lawyer and client may be shared by the law and may draw the lawyer away from a single-minded allegiance to the client’s point of view.

Throughout the case when the lawyer finds himself or herself estranged from the client, distant from the client, and unable to see the client’s point of view clearly, the lawyer can reorient himself or herself by focusing on the areas of overlap between the client and law.

Logistical Tips and Considerations

- Habits One and Two lists can be accomplished over time by keeping post-its or pre-made sets of blank rings in each case file and jotting similarities and differences as they come up.

- Lawyers can make Habits One and Two a part of the preparation for every interview, and continue to populate the rings or lists as the case evolves and the lawyer’s information about a client grows over time.

- Habit Two can also be done in stages. Dyads can be filled in during breaks in court, while waiting for the client to appear, or in the odd moment between phone calls. At other moments, looking at the rings and seeing what insights they offer can be done in more reflective or integrated moments.

- For lawyers doing the step-by-step approach, it may be useful to jot down notes reminding himself or herself to refocus attention on the client’s legal claim and his or her world as it’s affected by the claim.

- Experienced lawyers with large caseloads can acquire the “forest” impression of a case in less than a minute, by simply asking any one of these questions and impressionistically drawing the rings: (1) How similar am I to the client in this case? (2) How good is the client’s claim? (3) What agendas do I, as the lawyer, bring in with the law about issues relating to the case and draw those impressionistically?

- If time is short, lawyers can try just the circles in motion—even just drawing the circles from instinct with the overlap showing your sense of connection to your client. You might start with the client and the law, and your sense of the strength of your claim. Then you might add in your own circle. (In Jean’s child advocacy clinic, this was often a revelatory moment—we saw how closely aligned our circle and the law circle looked, and how much less overlap there was with the client’s world. This impressionistic view gave us insights. No wonder our client often saw us as “the man”!) This activity can literally take five seconds.

- Lawyers can try Habits One and Two from the client’s point of view. While having no illusions that we understand exactly how the client sees things, it may be a very useful exercise to put ourselves in our client’s shoes and see how we see things from that vantage point.

- Habits One and Two are most important when a case is particularly troubling or challenging to the lawyer.

- Lawyers could also explore using the law/client overlap as a guide for client counseling. Drawing the client-law circles with the client and examining areas of overlap to show the good parts of the claim, and examining the areas of difference to show points of separation between the client and the law, could help the lawyer begin to discuss legal strategies with the client. As an ongoing graphic, if useful to the client, the lawyer could use the law/client Venn diagram to help the client see changes in the legal case over time.

- Lawyers should not feel guilty or ashamed about having spontaneous negative thoughts about their clients. Their awareness will prevent those negative thoughts from becoming too important and may protect the client from others who act on those thoughts in the case.

Resources:

Susan Bryant & Jean Koh Peters, Chapter 15, Reflecting on the Habits: Teaching about Identity, Culture, Language, and Difference, in TRANSFORMING THE EDUCATION OF LAWYERS: THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CLINICAL PEDAGOGY Carolina (2014), 357 – 358.

Susan Bryant & Jean Koh Peters Chapter 4, The Five Habits of Cross Cultural Lawyering, in RACE, CULTURE, PSYCHOLOGY, AND LAW, edited by Kimberly Barrett and William George, Sage Publications (2004), 53 – 56.

Susan Bryant, The Five Habits: Building Cross-Cultural Competence in Lawyers, 8 Clinical L. Rev. 33 (2001), 68 – 70, 88 – 89.

Jean Koh Peters, Representing the Child-in-Context: Five Habits of Cross-Cultural Lawyering,

Slides

Habits Critical Incidents Questionnaire