Brief Description

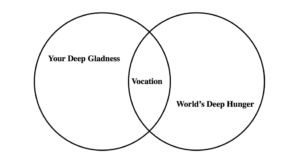

In choosing a career or path in life, many of us have struggled to find balance between what we want to do and what we think we should do. When we let go of arbitrary and external expectations and reach for joy and fulfillment, we can begin to explore our vocation. Theologian Frederick Buechner defines vocation as the place where “your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.” 1 Your deep gladness is the call of one’s true, enduring and authentic self, the pursuits that engender, not necessarily always happiness, but profound joy. The world’s deep hunger includes all the ills of the world that require justice or healing. Vocation is where we find joy in the pursuit of addressing the world’s deep hunger. Exploring and developing one’s vocation can free one from the competitive, career-focused life and towards a deeply meaningful, integrated daily life and legacy.

Clinical teachers working intensely with students one-on-one develop many insights into the vocations of their students. In this work, many teachers pursue their own vocations—of service, education, and solidarity to name a few—through the great joy of daily engagement with students and clients. For teachers, students and lawyers seeking to discern their vocations, Jean offers these thoughts. She and Mark Weisberg explored these ideas for teachers specifically in their chapter on The Teacher and Vocation in The Teacher’s Reflection Book. This post draws heavily from that chapter. 2

Understanding Vocation

What if you had nothing to prove? What if you undertook every class, every article, every meeting, every student and collegial interaction, with no concern about proving anything to anyone? Would you be living your professional life as you now do? Would you work as you now work? Maintain the same relationship between your professional and personal lives? To answer these questions would be to express what for you would be a life lived in vocation, a life unburdened by trying to fulfill the external expectations imposed, or that we imagine to be imposed, by others.

Yet many of us do find ourselves being governed from the outside, by fear of failing, disappointing others, or looking foolish. We try hard to please others; we measure our success by external standards. For many of us, these barriers to living in vocation persist throughout our lives.

What does it mean to lead a life in vocation? Buechner believes vocation to be that “place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.”

Your Deep Gladness: The Call of the True Self

For each of us, our deep gladness, that which gives us abiding, profound joy, is the call of our true self, where our history, our enduring loves and values, and our both established and evolving identity can be explored and celebrated. The call of our deep gladness invites us to look beyond the quick fix, peer pressure, or the urgent agendas of others to a truth deep within ourselves. To look within ourselves, to our identity, or core, suggests that when we find our deep gladness, it will sustain us in both good times and bad. In that way it differs from happiness. The joy of deep gladness does not depend on us enjoying good luck, good times or smooth sailing. This is the joy that keeps us grounded, content, at peace with ourselves, even in turbulent times.

Embracing our joy isn’t always simple. Many of us are accustomed to putting our desires and ambitions on the backburner because of our responsibilities and obligations to others. Vocation does not require us to abdicate those responsibilities, but to make informed choices that prioritize our joy. Vocation does not require that we all work in the public interest sector or work without sufficient financial support. Instead, vocation puts a focus on personal joy while still making the decisions that are holistically right for us.

Lawyers who begin their careers with substantial obligations to family as well as their own debt often ask whether they are truly free to pursue their vocation. In talks with first-generation professional students and students of color at Yale, Jean often shared her own experience of abruptly quitting her planned job at a New York corporate litigation firm and instead pursuing her deep gladness (representing children) leading to great financial problems (deferring her maxed out student loans at 100% interest for a year). In addition, she was deemed ineligible for her law school’s low income protection program, a blow that started her career on very shaky financial footing. In the end, she and her husband paid off every penny of the debt while working deeply within their vocations. Throughout the process, Jean has attested to her students, she became convinced that she was not only actively seeking and pursuing her vocation; in fact, she became sure, her vocation was actively seeking and pursuing her, consistently rewarding leaps of faith with the wherewithal to live comfortably despite the financial challenges.

Joy is self-validating. Joy also can be mystifying. We may not know why we find it so enjoyable to play tennis, put together a jigsaw puzzle, or bake a loaf of bread, or why the sight of a beautiful painting in a museum, or the sound of our favorite music on the radio lightens our heart, even on the most difficult day. But these examples suggest the joy Buechner is describing and inviting you to identify. The joy that is not located in any single moment or particular context, but the joy that motivates you today as it did ten years ago, and as you have reason to believe, will continue to do so ten years from now.

The World’s Deep Hunger: Which Call? Whose Call?

The call of the world’s deep hunger is vast and multi-vocal. For each of us to try to answer its many voices is impossible. So, as vocation invites you to identify what that call is for you, it also invites you to give yourself permission not to answer all the calls that you hear.

How would you encapsulate what for you is the call of the world’s deep hunger? For lawyers, we might think of it as the call of justice. For doctors, would it be the call of healing? For artists, the call of beauty?

Teachers hear many calls—calls from their subject matter, calls from their educational mission. What speaks to you: the call of understanding, or discovery? The call of learning? The call of your discipline? The call of creativity? Take a moment to consider how you would summarize, in a word or phrase, the call(s) that most compel you.

In addition to finding your call, vocation may compel you to identify those calls of the world’s deep hunger that you cannot answer, and to forgive yourself for not trying to answer them. In our media-saturated times, doing this can be difficult. What are the calls you constantly hear that tear at your heart but cannot be answered now? For many of us who have revered the medical profession but lacked all the skills required for this call, we must let go of the aspiration of being a great surgeon or of curing breast cancer. Or those of us who loved writing stories when we were young may not be able to become the next J.K. Rowling. Sorting through the calls of the world’s deep hunger is a constant challenge, but no challenge is greater than that of daring to hear the sounds of the world’s calls as you search for the ones you can authentically answer. (One major consolation: we may find it part of our vocation to support enthusiastically our friends, students, and colleagues who find joy and serve deep hunger that we cannot address.)

In fact, your gladness may help you hear the call more clearly. In this information age, we worry less that the call of the world’s deepest hunger will reach you, and more that the cacophony of anguish will overwhelm or numb you. Joy’s ear may help you tune in to the cries you can hear and answer best.

Where Your Deep Gladness and the World’s Deep Hunger Meet

Vocation is where your deep gladness intersects with the world’s deep hunger. In your vocation, you can undertake a joyful daily life that addresses the calls that you can answer.

The path of vocation requires you to recover and experience your deepest joy daily, and to offer it in service of the calls that move you most—justice, healing, understanding, beauty, learning—whatever you designate. And delighting in the service of the most compelling will certainly evolve for you, perhaps looking vastly different in one season of life than the next.

Implications of a Life Lived in Vocation

Vocation implicates our deepest beliefs, our relationships, and our spirit. When we speak of our professional life, we tend to frame that conversation in terms of a career. By contrast, theologian James Fowler suggests that framing our life in terms of vocation would radically reorient our self-understanding. 3 Fowler offers seven liberating implications of living a life in vocation instead of a life in career. The following chart juxtaposes Fowler’s views on a life in vocation to a life focused on career:

|

CAREER |

VOCATION |

|

Who am I? What’s in teaching for me? |

Whose am I? Who am I working for? (James Fowler) |

|

Vindicating our worth through achievement |

Nothing to prove |

| Success is zero sum, won through competition, over the defeat of others.

Other talented, like-minded people are our rivals for scarce resources, jobs prestige. |

1. Called to an excellence that is not based on competition with others. Called to a vocational adventure that is distinct from that of anyone else.

2. Freed from anxiety about whether someone else will beat us to that singular achievement that would have justified our lives. 3. Freed to rejoice in the gifts and graces of others. In vocation we are augmented by others’ talents rather than being diminished or threatened by them. An ecology of giftedness. |

| Seeking skill, talent, opportunity, money; “dying with our options open”; limits are frustrating, must be overcome. | 4. Freed from jealousy and envy, we are freed from the sense of having to be all things to all people. In vocation we can experience our limits as gracious, even as we can experience our gifts as gracious. |

| Work and home are separate; work comes first. Maximize billable hours. | 5. Freed to seek a responsible balance in the investment of our time and energy. Vocation is the opposite of workaholism (vocation encompasses career and home, and daily life). |

| Time is our enemy—too much work, too little time. | 6. Freed from the tyranny of time. Time is our friend. |

| Personal Life is private and separate, shouldn’t interfere with work. | 7. Freed to see vocation as dynamic, as changing its focus and pattern over time, while continuing as a constant intensifying calling. |

In universities and courthouses, for example, we tend to measure our successes comparatively. Our differential salaries reflect judgments of our “merit.” We compete against each other for a fixed pool of financial resources. We measure ourselves by our success at winning cases or being published in the most prestigious journals. And we pass that competitiveness on to our students and successors.

In vocation, since we have nothing to prove, and since each vocation is unique, we aren’t competing with each other. Everyone is following their own path, a path they have no need to justify. Consequently, rather than ranking ourselves and others, we’re free to recognize, enjoy, root for and feel enriched by each person’s gifts.

In a world of infinite gifts, we “are freed from the sense of having to be all things to all people.” 4 Instead, we can welcome, even embrace, our limits, as well as our own gifts. Our vocation is dynamic. As we grow and develop, so will our vocation. While remaining a constant calling, its shape and texture may change, reflecting the changing patterns in our lives.

Sample Vocation Lesson Plan

Before Class

- Assign the worksheet (reproduced below) to students for completion prior to class.

Worksheet

-

VOCATIONAL DISCERNMENT WORKSHEET

Critical Incidents: Six Things That I Am Confident that I Do Well, and Enjoy Doing

(ideally from both Inside and Outside Law) (e.g., baking an apple pie, reading to a child, one-on-one basketball, gardening, speaking with clients, solving problems etc.) write the first things that come to mind:Now circle the one (if there is one) that stands out from the others as highest in enjoyment, confidence or both; the thing you feel most clearly and unambivalently is one of your standout talents.

Five Challenges facing our World that Deeply Trouble Me

(e.g., global warming, ongoing race bias, gridlock in Washington, etc.)

If you think of too many, preference the ones that you find yourself returning to again and again.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Now circle the one that most troubles you at this moment.

Critical Incidents: Three Things That I Am Sure to Do in My Life as a Lawyer or Law Student Which I Currently Dread And/Or Fear Doing

write the first things that come to mind:

Now circle the one (if there is one) which clearly stands out: the one you fear or dread the most or the one which, if resolved, would be the biggest breakthrough for you.

Introduction to Vocation

- Introduce exercise and explain your vocation story.

- Example: This exercise forced me to acknowledge things that I am good at. It also opened up the space to think about whether what I fear in the law is something I may actually want to do. I considered whether the things I fear are actually scary or just something that I didn’t want to try. What does vocation mean for me now? Vocation helps me think about whether I am challenging myself in ways that also brings me joy, as opposed taking on challenges that make me miserable.

Exercise Debrief

- Spend 15 minutes discussing the exercise with about 5 minutes in each part

- Encourage participants to share anything they want to share – the things they are good at, what they fear, etc.

- Remind participants that there is also no pressure to share if they are uncomfortable.

Things We Are Good At

- Was this challenging?

- Anything that came easy?

- Any trends that came up for you?

Problems in the World

- Was this what you expected it to be?

- Did there feel like there were too many problems?

- Was it easy to focus on which one bothers you the most?

Fears Anything you found challenging?

- Were you surprised by what you circled?

- What did you notice about where you went with this exercise?

Can The things you’re good at help you resolve your fear?

- Concretely, how do you accomplish one of the things you are good at?

- For instance, I am good at making an apple pie. I clean my work area, I make sure I have all my ingredients handy, I put on quiet music, I work methodically on one thing at a time.

- Can any of those concrete ideas help you with my fear?

- For instance, I fear writing. But now that I think of it, I often work in a messy area, I don’t have my sources around me, my door is open and I hear a lot of hallway noise, and I often flit from thought to thought and task to task. So what if I try writing the way I make an apple pie: clean my desk; gather my sources first; play quiet music; and try to focus on one task at a time.

- So: try applying the method of the item you circled in 1 to the fear you circled in 3.

Closing

- The goal here is to identify what is challenging and use what we know we are good at as a potential source of strength when facing challenges and making vocational choices. In addition, our confidence in the items that bring us joy can give us a critical incident to explore: how can the minutiae of the things that I love and am confident in instruct me as I face my fears in my professional life?

Additional Vocation Exercises

We encourage lawyers, teachers, and students to utilize the following exercises when exploring their vocations. They can help with identifying, understanding, and possibly, more thoroughly embracing vocation.

Write Your Obituary or Eulogy

One way to discover your path might be to begin at the end and explore what you’d want said about you at the end of your life. Jean remembers first doing this exercise as a teenager at her family camp, and the huge impact it made on her perspectives at the time. Take some time with your journal and compose either your obituary or a eulogy for your funeral. If they help, use the following guidelines:

- Don’t fret about any detail (which newspaper, what length, the identity of the author, the date of the article or speech) unless it sparks your creativity. If a choice of detail blocks you, choose the least anxiety-provoking alternative and keep writing;

- Beyond grounding the basic facts in reality, feel free at any point to reach into imagination or fantasy;

- If you get stuck, observe what stimulates your writing and also what impeded it, and go back to step a.;

- Hang in there. When you’re finished, explore whether you’ve found some meaning in your life independent of the need to have proven yourself to the world.

Find and Explore a Governing Metaphor

As a way into “the mystery of our selfhood,” Parker Palmer invites us to fill in the blank in the following sentence: “When I am teaching at my best, I am like a _______.” 5 He suggests you “accept the image that arises, resisting the temptation to censor or edit it.” 6 Palmer writes:

When I am teaching at my best, I am like a sheep dog—not the large, shaggy, lovable kind, but the all-business Border Collies one sees working the flocks in sheep country. . . My task in the classroom, I came to see, parallels this imaginative rendering of the sheepdog’s task. My students must feed themselves—that is called active learning. If they are to do so, I must take them to a place where food is available: a good text, a well-planned exercise, a generative question, a disciplined conversation. 7

Try writing a governing metaphor for yourself.

Compose a Job Description

Compose a job description that reflects your clearest sense of your task. Not the task that someone or some institution has imposed on you, but the one you’d choose if you had nothing to prove, no debts to repay, and no obligations to others. Consider the questions: What are you doing? What are you really doing? What is your deepest sense of call? What is your true vocation?

How does it compare to what your institution or employer would write? If they differ, can you imagine doing your job as you’ve described it for yourself? What would change from how you now work? What would remain?

Write or visit Your Future Self

We can benefit from writing letters to ourselves, written in a lucid moment or a moment of transition to yourself as a fixed point in the future. Have a friend or colleague keep it and send it to you. It can remind you of deep commitments and insights over time. You can also expand this exercise to your students, by collecting their letters to their future selves at the beginning of a school year and sending them back at a midpoint.

Karen Saakvitne and Laurie Pearlman, in the context of managing vicarious trauma, have created a remarkable Future Self Visualization 8 that facilitates a visit with your future professional self. Jean has recorded a slightly modified homemade version (recording forthcoming).

Summary Points

- Find vocation at the intersection of your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger.

- In vocation, since we have nothing to prove, and since each vocation is unique, we aren’t competing with each other.

- Vocation is dynamic. As we grow and develop, so will our vocation. While remaining a constant calling, its shape and texture may change, reflecting the changing patterns in our lives.

- Keeping your vocation in focus brings meaning to our daily life and strength and clarity, even joy, to difficult times. Use exercises to explore and evolve your vocation as an ongoing practice.

- Clinical teachers are uniquely equipped to reflect with law students on their vocations and the role of law in their lives.

Notes:

- Frederick Buechner, Wishful Thinking: The Seeker’s ABCs 119 (1993). ↩

- This webpage draws substantially from a chapter in Jean’s book on teaching. See Jean Koh Peters and Mark Weisberg, A Teacher’s Reflection Book: Stories, Exercises, Invitations (2011). ↩

- James W. Fowler, Becoming Adult, Becoming Christian: Adult Development & Christian Faith 83-85 (2000). ↩

- Id. at 130, n. 4. ↩

- Parker J. Palmer, The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life 148 (1998). ↩

- Id. ↩

- Id. ↩

- Karen W. Saakvitne and Laurie Anne Pearlman, Transforming the Pain: A Workbook on Vicarious Traumatization (1996) ↩